By: Sarah Brown, Ph.D.

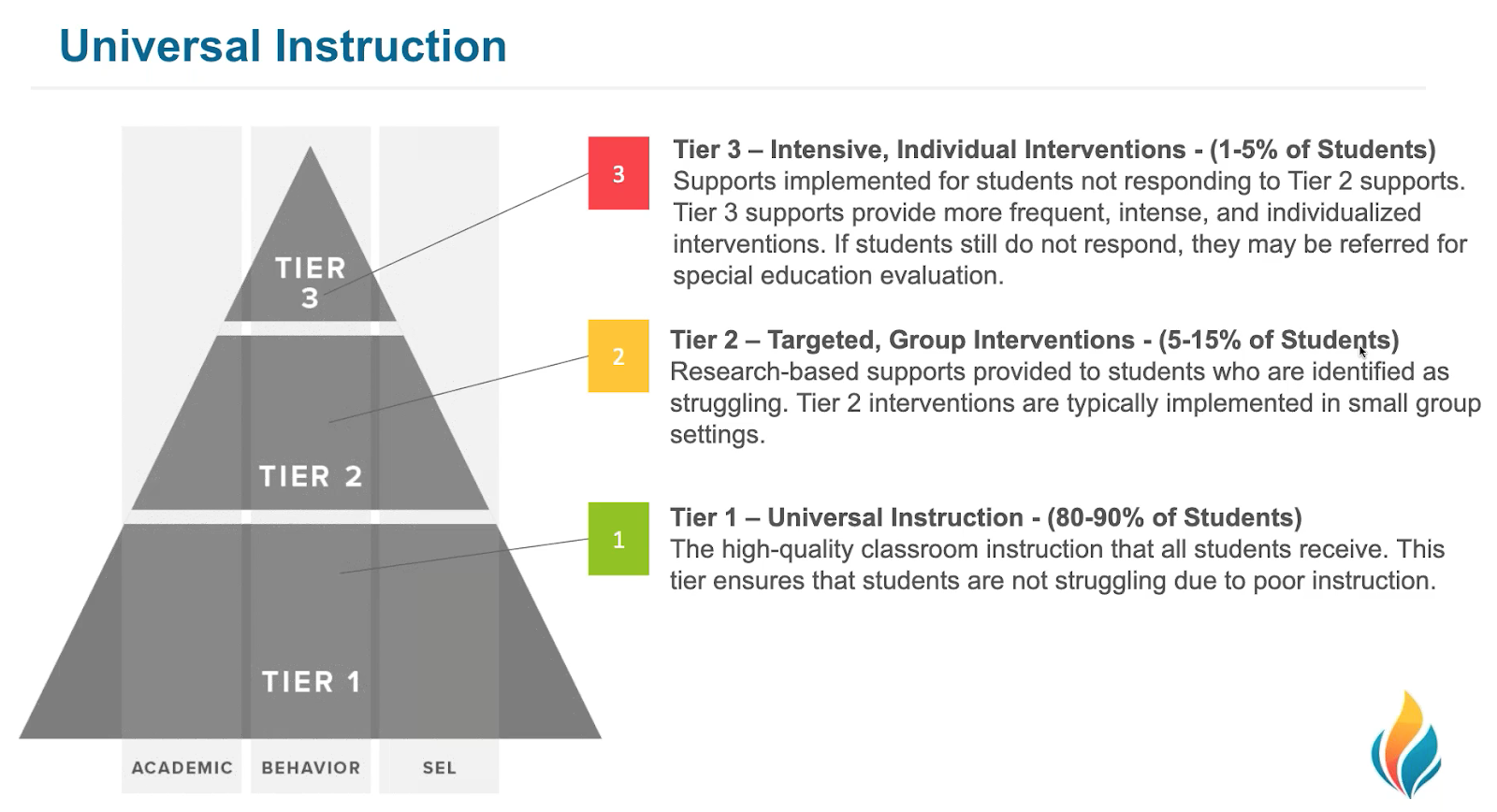

Have you ever had food poisoning? If you have, you can attest that it is an unpleasant experience, to say the least. On the other hand, more often than you have food poisoning, you likely have food that isn’t bad, it just doesn’t taste as delicious as you’d hope and expect. Maybe it’s bland, or too spicy. Maybe the combination of flavors is lousy. In those cases, the food can be improved and, hopefully, even made pleasurable to eat. Similarly, core instruction, or the universal tier can be improved. However, that doesn’t mean it’s broken. Many times, schools implementing a Multi-Tiered System of Support (MTSS) see their pyramid looks more like a toy top, and have believed that their core is broken. It does not need to be replaced, but, may need to be given extra attention and some additional improvements. Universal screening data are an essential component of identifying when a universal tier may need spicing up. An MTSS is about using data to help determine how to best utilize resources to meet the needs of students in the school today.

What is the Universal Tier?

The universal tier, also called core or Tier 1, is the standards-based instruction provided to all learners in a school. Universal tier instruction includes the materials, instructional practices, and time that are designed to help students meet grade-level standards. It also includes the differentiation teachers provide to support all students daily. Because all schools are different, the universal tier looks differently in each school. It must be flexible to meet the variety of student needs in the building in any given year in order to support students to learn grade-level standards.

What is a Strong Universal Tier?

In most schools, a strong universal tier will result in about 80% of students meeting expectations without additional intervention. The other 20% of students will need additional instruction, in the form of supplemental or intensive interventions, in order to work toward proficiency. A common misconception is that the MTSS pyramid suggests that 80% of students should reach proficiency. When considering the strength of core instruction consider the pyramid to represent the resources (instruction, assessment, interventions, etc.) that are needed to help all students meet the standards. In reality, the ultimate goal is for teachers and schools to work toward supporting all students to reach proficiency. But, there are factors that the school cannot control that will also influence student outcomes. Mostly likely there will be students who do not meet those ambitious goals, however, many of them will make important gains with additional resources.

Rationale for a Strong Universal Tier?

Schools need a robust universal tier in order to meet the needs of all students. Schools rarely have the resources to provide effective, intensive intervention to large numbers of students. An effective universal tier allows for supplemental and intensive instruction to be targeted and agile for the students who need it. When schools have more learners who need intervention than they have resources to provide the intervention to, ineffective practices emerge. Some often seen include shortening the intervention period so more interventions can be delivered, or decreasing the frequency of the intervention to offer more interventions. The table below depicts the impact of those changes. As intervention frequency and duration is decreased, the instruction is decreasing. In those cases, schools cannot expect students to make ambitious progress in an intervention that was not delivered ambitiously. Thus, without a robust universal tier, many learners will not achieve their goals. It will not be possible for the intervention system to keep up with the needs of learners.

Assessing the Strength of the Universal Tier

Universal screening data are the best way to assess the strength of the universal tier. In Iowa, there are two questions schools ask to identify the strength of their universal tier using universal screening data (Iowa Department of Education, 2016). The first is, “What percentage of students are on-track?” We look at these data first as an entire building, then by individual grade levels and subgroups. In FAST™, the Group Report (shown below) provides the information needed to answer this question. Students who are in the College Pathway and Low Risk levels are considered on-track, while students who are in the Some Risk and High Risk levels are considered not on-track as they are learners who might require additional instruction to be successful.

FAST Group Report Example

FAST Group Report Example

The second question is, “What percentage of students who are on-track in the fall remain on-track in later screening periods?” The Impact Report (below) illustrates this information. When looking at this report, a teacher can see how many students who began the year at low risk or college pathway levels remained at those levels in later screening periods. When students who begin the year on track remain on track, it does not mean that they did not learn or did not grow. Instead, it means that the universal tier was strong enough to ensure the learner made enough progress throughout the year to remain on track during another benchmark period. In the example below, two students, Aylin Ratke and Bertha Wisoky did not make enough progress between the fall and winter screening periods to remain on track. Schools aim to have at least 95% of learners who begin the year on track meet later benchmark targets. The target is high because the students who are included in this calculation are only those who began the year on track.

FAST Impact Report Example

FAST Impact Report Example

How Can the Universal Tier be Improved?

When universal screening data indicate the universal tier needs improvement, schools have several things to consider. First, consider whether the practices that are intended to be in place as part of universal instruction are occurring. Essentially, did the school follow the universal tier recipe? Second, the school might consider adding additional evidence-based practice to the instruction provided as a part of universal tier instruction. An evidence-based guided practice routine may be just the spice needed to boost student learning! Last, schools could stop the use of less effective strategies and those strategies not adding to student learning. Swapping out low-quality ingredients for more high-quality ingredients is a great way to improve the outcomes of universal tier instruction.

Summary

A strong universal tier supports the ability of schools to meet the needs of all students in a sustainable manner. When used at a system level, universal screening data allow for schools to identify the effects of current universal tier practices. When a team discovers that the universal tier resources aren’t having the intended effect, leaders can prioritize resources to be shifted toward improving the universal tier. Spices can be added in the form of evidence-based instructional practices. Less successful practices, and those not shown effective by research, can be replaced. Staff learning time can be prioritized to focus on improving universal tier instruction. And then, universal screening data can be examined again to celebrate the growth demonstrated by the targeted system improvement efforts.

Reference

Iowa Department of Education (2016). Universal Instruction Protocol. Retrieved from https://www.educateiowa.gov/documents/accreditation-program-approvals/2016/05/universal-instruction-protocol on October 10, 2016.

Sarah Brown, PhD, is the Chief for the Bureau of Learner Strategies and Supports at the Iowa Department of Education, where she leads statewide implementation of MTSS for the state of Iowa. Prior to joining the Department of Education, Dr. Brown served as a Unique Learners’ Manager at the St. Croix River Education District (SCRED) in Minnesota and worked for several years at Heartland AEA 11 in central Iowa, a world-recognized leader in MTSS practices. She is interested in improving systems to support high achievement for each and every student.