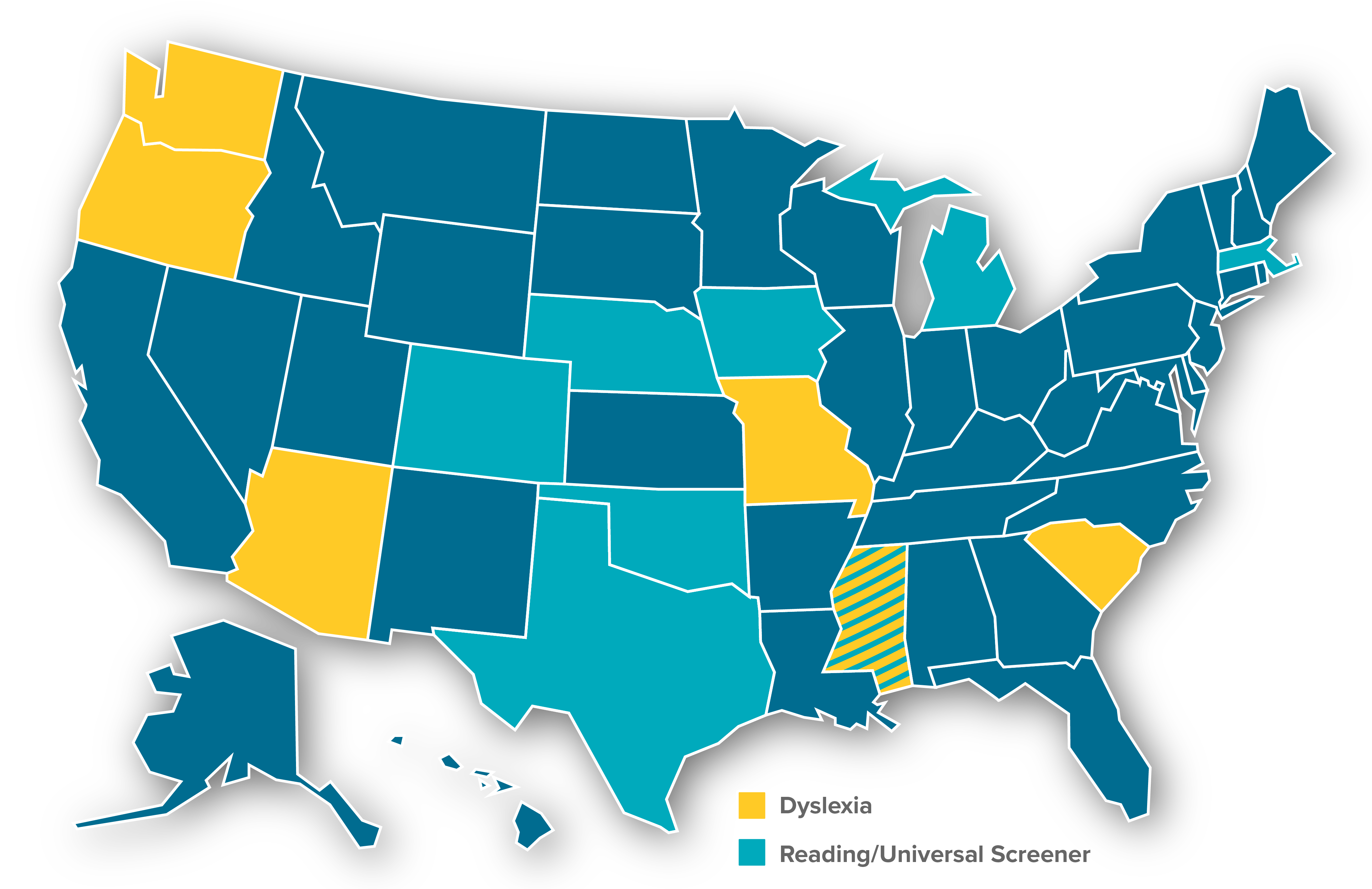

The term dyslexia has become more widely used in recent years, in part because many states have passed laws requiring dyslexia screening. Such laws are designed to identify possible signs of dyslexia as early as possible because the most effective treatments work best when implemented as soon as possible.

(We discuss ways to leverage legislation to improve screening dyslexia screening and intervention in here.)

Many parents and educators might wonder “what is dyslexia?” and “what are its indicators?” And, they might want to learn more about available treatments and why screening is important. This post will address these questions as well as provide additional resources about dyslexia.

What is Dyslexia?

The term dyslexia was originally interpreted to mean “word blindness” but that is not what it means in terms of reading difficulties. Instead, dyslexia involves difficulty reading due to poor phonological processing. The following is the definition adopted by the International Dyslexia Association (IDA; 2019):

Dyslexia is a specific learning disability that is neurobiological in origin. It is characterized by difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition and by poor spelling and decoding abilities. These difficulties typically result from a deficit in the phonological component of language that is often unexpected in relation to other cognitive abilities and the provision of effective classroom instruction. Secondary consequences may include problems in reading comprehension and reduced reading experience that can impede growth of vocabulary and background knowledge.

Although dyslexia has most likely been present since the origin of written words, it did not become an identified condition until the nineteenth century when the ability to read became more important. In the U.S., most states introduced compulsory school attendance laws in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. When school attendance became mandatory, those students who might have stayed at home due to difficulty learning to read were now required to attend school.

As more children began attending schools, teachers noticed that some had greater difficulty learning to read.

In the 1920s Dr. Samuel T. Orton, a U.S. physician, began a conducting research to understand why some children had difficulty learning to read. Although some of the hypotheses Dr. Orton developed were not confirmed by later research, his work was instrumental in creating an awareness of reading disabilities and eventually led to the founding of the Samuel T. Orton Society, later renamed the International Dyslexia Association.

(Click here to learn more about the history of the organization.) One of the lasting effects from Dr. Orton’s work was the development of assessment and instruction methods for identifying and treating dyslexia. Later researchers confirmed the basic features and indicators of dyslexia as well as how best to identify and treat it (see Shaywitz, 2005).

Indicators that Suggest Dyslexia

Research now confirms that there are very specific indicators (e.g., symptoms) that suggest a student has dyslexia. As noted in the IDA definition, dyslexia is primarily caused by deficits in linking the sounds that go with the letters used in text.

Being able to match specific sounds to the letters that represent those sounds is called phonological awareness, or phonics. It is important to note that not all languages use sound and symbol correspondence for individual letters that make up words.

The languages that rely on matching sounds to letters in order to compose words and sentences are known as alphabetic languages because they use a distinct and unique set of letters and sounds. Some languages have only oral components and others use a system of where one character (or picture) depicts an entire word. Languages that use characters or pictures for an entire word are known as logographic.

Available Research about Effective Reading Instruction

Since English is an alphabetic language, research about difficulties in learning to read in English examined how mapping the sounds linked to letters might contribute to becoming a proficient reader. The available research about effective English reading instruction, as well as factors associated with reading difficulties, was summarized in a major study commissioned by the U.S. Congress and published in 2000. Congress commissioned the National Reading Panel (NRP) to review available research about effective reading instruction as well as what factors contribute to reading difficulties.

The panel published its report in 2000 and identified five core components to English reading skills:

Phonemic awareness: the ability to identify the individual sounds that make up words;

Alphabetic principle (e.g., phonics): the ability to attach the correct sound to each letter or combination of letters in order to decode and blend letters into words;

Fluency: the ability to read words and sentences accurately, automatically, and with prosody that recognizes punctuation and intended phrasing;

Vocabulary: knowledge of the meaning of individual words, including multiple meanings when applicable;

Comprehension: understanding sentences, paragraphs, and longer passages of fiction and nonfiction in relation to the author’s intended meaning.

The NRP report noted that effective readers need to develop mastery of all five identified core reading areas. Students who struggle to learn to read most often experience difficulty with the first two core areas: phonemic awareness and phonics. As a result of these difficulties, they later develop deficits in fluency and comprehension.

Notably, not all students who struggle with reading demonstrate problems with vocabulary. As indicated in the IDA definition and Shaywitz (2005), dyslexia involves a chronic difficulty with detecting the individual sounds in words as well as mapping those sounds to the specific letters that represent the sounds in print.

The Experience of Students with Dyslexia

Due to the importance of reading in all areas of school, students who struggle to master basic reading skills are likely to avoid reading assignments unless treatment is provided. Most children enter school eager to learn and anticipating success. For students with dyslexia, difficulties can appear as soon as the instruction focuses on the phonological components of reading.

Specifically, such students struggle to understand the distinct and different sounds in spoken words. In addition, they fall behind when trying to connect these sounds with the corresponding letters in print.

Some students with dyslexia are able to compensate for these difficulties through careful attention to the overall ideas presented in oral and written text. Such attention can suggest that a student has generally good text understanding, even if decoding and fluency skills are weak.

Compensation through generally strong comprehension might be an effective strategy in the primary grades (e.g., K-3), but in upper elementary and secondary grades, students are expected to read increasingly longer texts on their own. At this stage, students with dyslexia struggle to keep up with the number of pages assigned because their fluency is weak.

Treatments

The good news is that there are treatment methods to assist students with dyslexia. The defining characteristics of effective treatments are direct and systematic instruction of phonemic awareness and sound-symbol correspondence. In a recent review of prior research, Stockard, Wood, Coughlin, and Rasplica Khoury (2018) documented that a method known as direct instruction (DI) led to significantly better reading outcomes than other teaching methods.

It is worth noting that DI has been shown to be an effective treatment for students with dyslexia as well as those demonstrating other reading skill deficits. This is important because segregating certain students for instruction (i.e., those with dyslexia) can be both expensive and stigmatizing. Using reading instruction practices that help all students learn means that schools can provide effective solutions for all students in the same classroom.

Such methods will work best when provided in the early elementary grades (e.g., K-3). If students do not receive such instruction in the early grades and continue to struggle with reading in later grades, more intensive and individualized treatments are typically needed.

Role of Screening

Although there are treatments for dyslexia that can be effective for students of all ages, research has shown that early intervention is the best way to help students with dyslexia be successful. The core components of dyslexia involve the essential early reading skills of phonemic awareness and phonics. For this reason, efforts to support students at risk for dyslexia at the earliest stages of reading instruction are important.

Such efforts can help students develop decoding and word attack skills that will foster easier acquisition of the more advanced reading skills such as fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. In order to know which students are at risk of dyslexia and require early intervention and direct instruction, the best practice is to conduct universal screening of all students.

Such screening involves testing students’ recognition and production of the sounds in words (e.g., phonemes) as well as how automatically they recognize letters and objects. These screenings take about five minutes per student. Those students whose screening scores indicate risk for dyslexia and related reading problems can complete additional assessments that will confirm their needs.

Upon confirmation, students at risk will benefit from direct and systematic reading instruction.

Additional Resources

The following websites provide information about dyslexia and reading instruction for parents and teachers.

- International Dyslexia Association: https://dyslexiaida.org/

- Meadows Center Reading Institute: https://www.meadowscenter.org/institutes/reading-institute

- National Center for Learning Disabilities: https://www.ncld.org/

- Reading Rockets: http://www.readingrockets.org/

References

International Dyslexia Association. (2019). Definition of dyslexia. Retrieved from: https://dyslexiaida.org/definition-of-dyslexia/

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH, DHHS. (2000). Report of the national reading panel: Teaching children to read: Reports of the subgroups (00-4754). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Shaywitz, S. (2005). Overcoming dyslexia: A new and complete science-based program for reading problems at any level. New York: Vintage.

Stockard, J., Wood, T. W., Coughlin, C., & Rasplica Khoury, C. (2018). The effectiveness of direct instruction curricula: A meta-analysis of a half century of research. Review of Educational Research, 88(4), 479-507. doi:10.3102/0034654317751919