All students suffered learning loss as a result of spring 2020 school closures. However, some were impacted more than others. English learners (ELs) especially missed out on opportunities for direct, specialized instruction that is so critical to building language proficiency, and may have been quarantined in households where little to no English is spoken. You’ll need to assess EL students right away this school year to determine where they are at in their language practice, what skills they are struggling with and what supports they need to keep building proficiency.

When assessing ELs, it is important to remember that this population participates in testing for a variety of purposes, several of which do not apply to their English-speaking peers. For those assessment purposes which span both groups of learners, specific assessment practices should be followed to ensure ELs’ success. Learn the importance of assessing ELs, the types of assessments to use, and practices to consider when measuring ELs’ language proficiency, content knowledge and academic achievement.

Why We Need to Assess ELs

Ask an educator to list the assessments they use in their classroom, and the list would be quite long. Ask an educator to share the reasons why we assess students, and that list would narrow considerably. There are three main reasons educators assess students:

- To identify and place students for specific support programs

- To monitor student progress

- To provide accountability metrics to stakeholders

We will examine each of these in turn and their relationship to ELs as compared to native English-speaking students.

Using Assessments to Identify and Place ELs for Specific Supports

As part of an enrollment process in a new state or school district, families complete a home language survey. Based on the information provided, some students will complete a series of assessments to determine whether they should receive support services for English language acquisition, and the extent to which those services should be provided. This type of assessment measure is akin to a universal screener, with the exception that it is gated and used only with students’ whose home language is not English. Many states have developed their own eligibility tests, while others use screeners from ELPA21 or WIDA.

Using Assessments to Monitor EL Progress

Educators monitor all student progress, all the time. They do this to determine present academic achievement levels and to assess students’ understanding of content. These academic achievement tests not only include standardized measures with clear benchmarks and norms, but they also include a variety of assignments, quizzes and tests in content area classes. The ultimate goal is for all students, including ELs, to achieve academically at high levels.

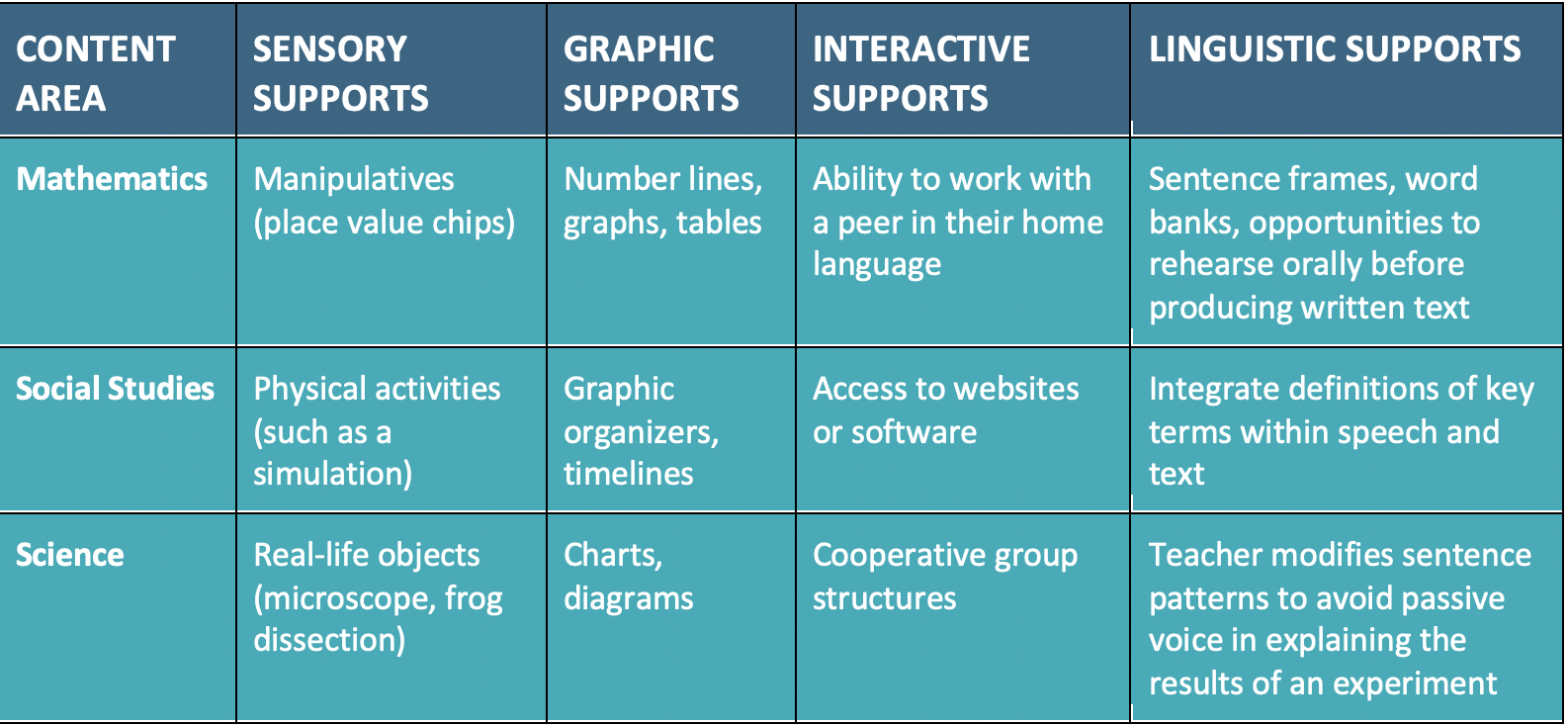

However, ELs’ language proficiency levels have an impact on their ability to demonstrate content knowledge. For students at lower levels of language proficiency, specific supports —sensory, graphic, interactive, and/or linguistic — are needed to measure student content knowledge and to assist them in their learning.

Here are some examples of helpful supports in three different content areas:

Even though ELs cannot necessarily communicate their content knowledge in the same ways as their native English-speaking peers can, they can still demonstrate similar levels of academic achievement when appropriate supports are put into place.

Academic achievement measures are not enough to adequately monitor EL progress because they only address one aspect of their learning. Educators also need to monitor ELs’ acquisition of the English language in each of the four modalities: reading, writing, listening, and speaking.

An Example:

Let’s take a look at an example of what this might look like in the areas of writing or speaking.

The science teacher, Ms. Jackson, wants to measure students’ understanding of animal adaptations. She asks them to explain, in writing or verbally, how adaptations help animals. Students are to include examples of animal adaptations in their responses, and the science teacher looks for students to ultimately understand that animals have specific adaptations to help them survive. For example, anteaters have long tongues so that they can reach deep into holes to extract insects. Without these long tongues, anteaters would have difficulty accessing a primary food source, and they would die.

Ms. Jackson has an EL co-teacher, Mr. Garcia. He examines students’ responses to the same question Ms. Jackson has posed to all learners. There are some key differences in how Mr. Garcia approaches his analysis, however. First, Mr. Garcia chooses to narrow his focus and only pays attention to responses from students classified as EL. Second, he uses a different rubric to evaluate students’ work; his rubric focuses on linguistic complexity, vocabulary usage and language control. This rubric is aligned to English language proficiency levels, so Mr. Garcia has an idea of how the ELs are performing and what instruction he and his co-teacher will need to provide to help them move toward higher levels of proficiency.

In terms of monitoring student progress in relation to reading proficiency levels, educators might use more formal measures, such as FastBridge’s Curriculum-Based Measures (CBM). Assessments such as earlyReading and CBMreading are valuable for this purpose. Measuring student progress with listening typically requires more informal methods.

Using Assessments to Stay Accountable to EL Growth

ELs and native English speakers alike participate in assessments for accountability purposes. These are generally large-scale, standardized measures with clear benchmarks and norms. Each year, students in grades 3-8 participate in state-level testing in the areas of mathematics and reading, as mandated by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) (2015). This type of testing also occurs once in grades 10-12; science achievement is measured a total of three times between grades 3-12 (ESSA, 2015).

For children classified as ELs, there are additional accountability measures in place to ensure progress in acquiring English. These students participate in annual exams to determine their proficiency levels in each of the four modalities; this data is then used to adjust the level of support provided. When students reach near-native English proficiency levels, they are reclassified and exit EL support services.

For students at lower levels of English language proficiency, academic achievement tests for accountability can be frustrating experiences. When possible, accommodations or modifications should be used as long as they do not affect the validity of the test. Some states allow extended testing time and small-group or individual administration for ELs. Others provide no additional support for this subgroup. It is important to consult your state’s policies around standardized testing and ELs as some may even allow ELs to use bilingual dictionaries. These state-level accommodations are designed to improve student performance and reduce the level of frustration ELs might otherwise experience.

Extend Instructional Supports to EL Assessment

ELs participate in even more testing than their native English-speaking peers since they complete both tests of academic achievement and English language proficiency. As such, it is important for educators to understand the different purposes these assessments serve and the different forms they take within classrooms. Noted EL scholar Margo Gottlieb (2006) states that “[w]hichever resources are afforded English language learners for instruction should automatically extend to assessment.” Whenever possible, this should be the goal of educators, as it leads to vastly improved experiences for ELs.

*** Learn how FastBridge assessments can help you better understand where EL students are at and what supports they need to continue building language and academic proficiency after a spring and summer spent learning remotely and social distancing.

Contact us today to talk with one of our assessment experts.

References

Every Child Succeeds Act (ESSA) of 2015, Public Law No. 114-95, S.1177, 114th Cong. (2015). Retrieved from https://www.congress. gov/114/plaws/publ95/PLAW-114publ95.pdf.

Gottlieb, M. (2006). Assessing English language learners: bridges from language proficiency to academic achievement. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

WIDA Consortium. (2013). Developing a culturally and linguistically responsive approach to response to instruction and intervention (RtI2 ) for English language learners [PDF]. Retrieved from https://www.wida.us/professionalDev/educatorResources/rti2.aspx.