During this period of remote learning, educators have been concerned with the possibility of learning loss in what is known as the “COVID slide.”

We hosted a webinar to discuss how teams can leverage spring data via screening and progress monitoring as ways to identify and support students during this time.

In that session, we’ve fielded some additional questions that we thought might be helpful to address for the rest of our audiences. The following is our response to four frequently asked questions.

What to do with students who haven’t been screened because they haven’t been online?

There may be students who can’t be screened for a variety of reasons. Perhaps they haven’t been logging into the learning systems or attending small and large groups, and they haven’t been responding to contact. Sometimes, frankly, you won’t know the reason why they aren’t participating. Nevertheless, you should continue to reach out. (And for cases in which you do know the reason, you want to do your best to mitigate that.)

Most schools are providing hot spots and devices for students who may need them to access instruction. Other times, it might be that students are simply not interested in learning. In those cases, you could try to engage them via different means such as hosting an online trivia game or streaming an educational video regarding a specific topic of interest.

The main idea is that no data is still data. For the students who can’t be screened because they haven’t been engaging, find ways to show them that you still care and want to support them during this time.

Can I use benchmarks and norms with remote screening data?

Yes, the norms and benchmarks are still valid. To provide more context, the benchmarks are derived from studies that used statistical methods to assess the accuracy of the assessment score at classifying students relative to end-of-grade performance at well-established standardized assessments.

The cut scores for “some risk” and “no risk” were selected to optimize that overall accuracy. The risk score was further divided into two categories: “high risk” and “some risk” range. Thus, the risk categories are to be interpreted from a criterion-referenced point of view, where the criterion is a well-established expectation of year-end reading and math performance.

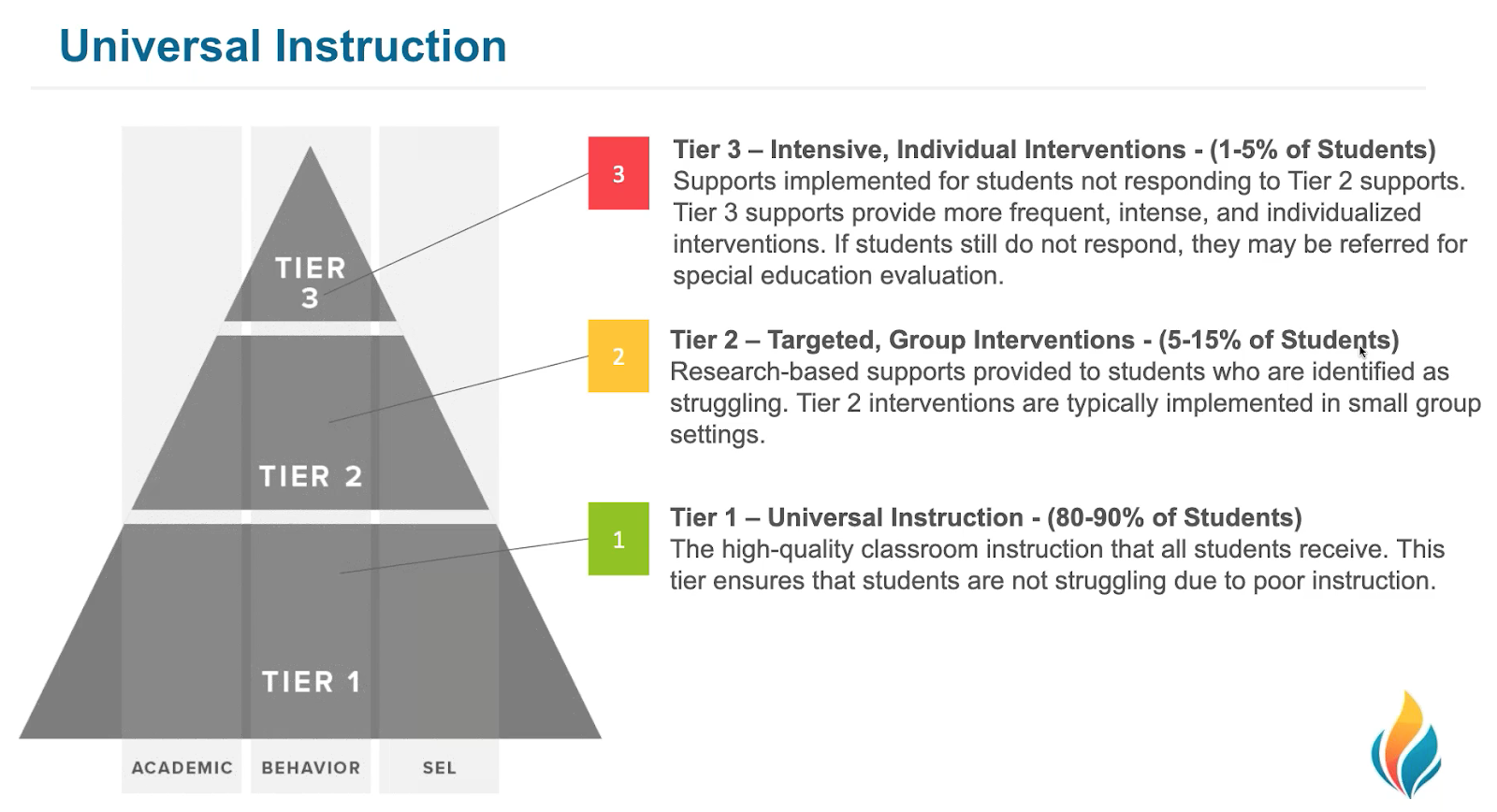

Additionally, a large corpus of research has shown that students classified as “low risk” are likely to meet end-of-grade performance expectations in schools that implement research-based core instructional programs with fidelity. Students with some risk typically require additional instructional support beyond core instruction to stay on track, and the research shows that students with high risk require intensive support to get back on track. So this interpretation does not change even with the circumstances. What is likely to change, however, is the percent of students identified as “at-risk” and this percentage is likely to go up for most schools.

While there is nothing typical about our current school situation, knowing how a student’s performance compares to what is typical is the best way to determine how learning is impacted under these unusual circumstances.

Should I adjust the benchmark?

No, you shouldn’t change the benchmark. Adjusting the benchmark to account for the likely performance decline only masks the level of need. There’s a large body of research that shows performance actually declines when expectations decline.

We understand a lot of schools use custom benchmarks. To really understand your data and where your students are at right now, it’s important to maintain continuity. You need to look at keeping those custom benchmarks that were established in the fall so you can evaluate performance against your original expectations. This will help you determine what the true impact was on student learning.

What if a student cheats on the screening assessment?

Certainly, educators have much less control over the testing environment when conducting assessments virtually. As such, it’s recommended for teachers to address this matter proactively as opposed to waiting until cheating occurs. There are two primary strategies to consider.

First, use the rapport and trust that you’ve already built with students to explain why the assessment is important. For instance, you can explain what it will and will not be used for, and why students need to take them in accordance with the same rules as in the classroom. The mutual respect will help them trust you when things seem uncertain.

Additionally, we recommend ensuring parents understand the purpose of these assessments. Explain why it’s important they’re taken in a standardized manner as they have been in the fall and winter. If parents understand it’s not just being used for a grade or to determine class placement (or other factors they might be anxious about), then they’ll be more willing to support you.

**** Would you like to learn more? Watch our recording of the “Preventing the COVID Slide This Spring” webinar on demand and register for Part 2: Preventing the COVID Slide with Back to School Readiness.