The COVID-19 pandemic has created many new challenges and opportunities for students and teachers. As schools across the U.S. work through how they will provide distance-based remote instruction for students, we know based on our conversations with educators in different districts and states, and from recent data pulled from the Education Commission of the States, that many different approaches and methods are being used. These range from districts telling teachers not to teach anything (i.e., no instruction) to video-conference-based lessons on a par with what students would be experiencing in the classroom.

The reasons for the varied approaches also seem to vary a great deal. According to teachers and parents in districts where no instruction is being provided, the reason is that the district is afraid of not meeting special education rules related to existing Individualized Education Programs. While the U.S. Department of Education and Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP) have issued guidance to schools that a fear of not meeting IEP requirements is not a reason to deny instruction to all students, this practice has still been reported (U.S. Department of Education Office of Special Education Programs, 2020).

Other remote instructional approaches include focusing on students’ physical and emotional well-being through nutrition programs and teacher check-ins related to student and family wellness. And some have initiated remote instruction that focuses on maintaining current skills without teaching any new content. There are some schools providing four to six hours per day of remote instruction, although most such cases are private schools.

As the duration of school closings and remote instruction has grown longer, some schools have shifted their remote programming to include a mix of review and selected new content. As districts proceed, it’s important to keep in mind the potential impacts various instructional decisions can have on long-term student outcomes. The most urgent matter for educators is how to help students whose current skills are behind their peers. By focusing efforts on students who need to catch up to grade-level goals, we can increase the likelihood they can start the next school year on track for success.

The Potential Impacts of the “COVID-Slide”

As discussed in this recent Education Week article, many educators are already talking about the inevitability of a “COVID-slide” as a result of the learning disruptions caused by school closures and instructional changes. This “slide” is analogous to the so-called “summer slide” that happens for some students over the summer months when school is not in session. Research on the summer slide indicates that some students lose a percentage of what they learned in the preceding school year over the summer because they are not practicing what they learned while away from school. Since the COVID-19 school closings started in the spring of the school year, and will now continue in many states through the end of the 2019-2020 school year, it is expected that some students will exhibit much greater losses and be farther behind when they return to school.

As the author of the article notes, the purpose of publishing “COVID-19 slide” data projections is to alert educators to how significant the learning losses could be if action is not taken immediately to provide remote instruction. Given the heterogeneity of approaches to remote instruction and learning that schools have adopted, it is very likely that there will be very significant and diverse effects of the school disruptions on short- and long-term student learning outcomes. The issue of “slide” or learning loss is even greater for students who were already performing below grade-level expectations when the closures began. For such students, the effects of a combined COVID+summer slide could result in losing an entire school year’s worth of learning.

Focusing on Catch-Up Growth to Prevent the Slide

As schools figure out what to teach for the remaining weeks of the 2019-2020 school year, and with consideration to the potential ramifications of the slide, one possible focus is on helping students whose current skills are behind their peers to catch up to grade-level goals so that they can start the next school year on track for success. The amount of work to implement online instruction for an entire school or district in a short period of time is very significant. Indeed, many teachers have reported that it is much more time-consuming to teach remotely than in traditional classrooms.

Nonetheless, the current circumstances mean that remote instruction is the only option available. Importantly, there is a body of research about effective online instructional practices that supports its use for learners of many different ages (Bernard et al., 2009). In addition, there is a very strong body of research about the types of instruction that students whose performance is below expectation need in order to catch up (Coyne, Kame’enui, & Carnine, 2010).

Given that both remote instruction and remediation lessons are effective ways of supporting students, perhaps schools should focus their instructional resources for the balance of the 2019-2020 school year on providing lessons that help students to catch-up to their peers. Catch-up growth refers to the amount of learning that a student needs in order to reach current grade-level expectations.

Catch-up growth is different from the typical growth that all students make during a school year. As noted by Fielding, Kerr, and Rosier (2007), those students who start out behind their peers will need to make bigger gains than other students in order to reach current learning expectations. Catch up growth is the opposite of the Matthew Effect (Stanovich, 1986) which documents how students who start out as poor readers will remain so unless they get additional instruction that helps them catch up to their peers.

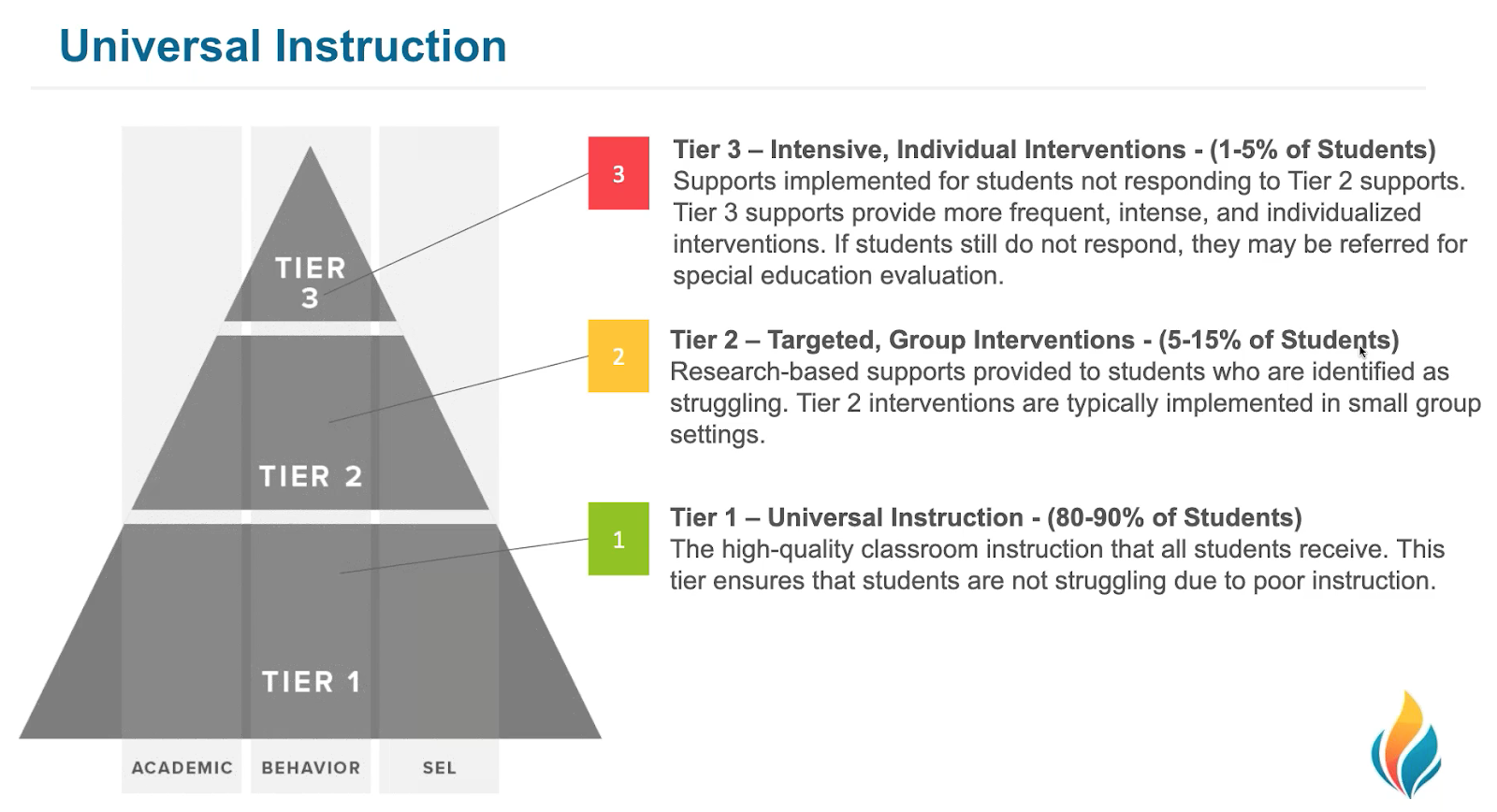

Importantly, catch-up growth can only happen if students are provided with additional instruction above and beyond the daily lessons provided for all students. Providing such extra instruction — also called intervention— is part of a Multi-Tiered System of Support (MTSS) that provides both effective Tier 1 core instruction and additional Tier 2 or 3 instruction for students who need it (Brown-Chidsey & Bickford, 2016; Gibbons, Brown, & Neibling, 2018).

Most every teacher will tell you that the biggest challenge in providing an effective MTSS is finding time in the day for the extra instruction that some students need. The current COVID-19 situation where students are at home and teachers are providing various types of remote instruction offers a very unique opportunity to provide the additional instruction that some students need if they are ever going to reach grade-level learning goals. Indeed, many students and teachers will tell you that the current pandemic has brought them many hours of time that goes unfilled with usual school activities. This unexpected gift of time can be harnessed to focus on providing students who need catch-up growth the additional instruction that might otherwise be impossible during a traditional school day.

Certainly, there are many logistics that are needed in order to make such catch-up lessons possible. These steps include identifying the students, ensuring that the teachers and students have the necessary computer equipment and internet access, gathering the instructional materials, and scheduling the lessons. Most of these steps are happening already in many schools across the U.S.

⇒ [FREE Webinars] How to Conduct Remote Screening and Progress Monitoring ⇐

It’s not clear whether teachers and their leaders recognize this very unique chance to harness this gift of time and transform it into the learning gains that some students need. Indeed, strategically using the time available due to COVID-19 to prioritize instruction for students whose prior data indicate a need to make catch-up growth offers the chance to reset learning opportunities for students who might otherwise remain indefinitely behind their peers.

As many educators know, students with significant learning gaps are far more likely to drop out of school. Such students include those with IEPs whose annual growth is not sufficient to reach grade-level performance; these students are even more likely than others not to complete high school. High school completion is a highly consistent and predictable indicator of not only employability but also mental and physical health and wellness. Those without high school diplomas are far more likely to be incarcerated (Sago, 2018).

Just like COVID-19 is a once-in-a-century event, the extra time for learning it offers students and teachers can be a once-in-a-lifetime gift for students who need catch-up growth.

****

Interested in learning more about how your team can identify and support students who are experiencing loss of learning now? Join our free 2-part webinar series "Preventing the COVID Slide" on May 7 and May 27 to unpack practical ways to engage remote learners in need of support this spring and this fall.

References

Bernard, R. M., Abrami, P. C., Borokhovski, E., Wade, C. A., Tamim, R. M., Surkes, M. A., & Bethel, E. C. (2009). A meta-analysis of three types of interaction treatments in distance education. Review of Educational Research, 79(3), 1243-1289. doi:10.3102/0034654309333844

Coyne, M.D., Kame’enui, E,J., & Carnine, D.W. (2010). Effective teaching strategies that accommodate diverse learners (4th ed.). Pearson.

Education Commission of the States. (2020, April). COVID-19 update: State policy responses and other executive actions to the coronavirus in public schools.

Fielding, L., Kerr, N., & Rosier, P. (2007). Annual growth for all students, catch-up growth for those who are behind. New Foundation Press.

Sparks, S. (2020, April 9). Academically speaking, the 'COVID Slide' could be a lot worse than you think. Education Week [blog]: Inside School Research.

Sago, R. (2018). Study finds about half of formerly incarcerated people have only a GED or high school diploma. Marketplace [audio recording].

Stanovich, K. E. (1986). Matthew effects in reading: Some consequences of individual differences in the acquisition of literacy. Reading Research Quarterly, 21, 360–407.

U.S. Department of Education Office of Special Education Programs. (2020, March). Individuals with disabilities education act: Questions and answers on providing services to children with disabilities during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak.